While the internet can be a gateway to knowledge, it can also be a source of significant disruption. For years my partner Bruce Baikie and I worked to build out internet connectivity in some of the world’s hardest-to-reach places, at the request of partners eager to experience a wave of educational and economic opportunities. But instead, time and again, we watched new and novice users sticking to the shallows of social media or simply giving up in frustration. Worse yet, many new users fell victim to scams, sexualization and disinformation.

No one is born knowing how to safely and effectively navigate the internet; it’s a skill set that must be learned and kept sharp. In order for communities to reap the benefits of the internet while limiting its risks, they must also have access to training that helps them build these skills.

Eight years ago, that lesson drove us to develop a solution to address this gap — providing offline communities with libraries of reliable and locally-relevant information while also helping them develop those crucial internet-ready skills. So it pains us to see over and over again that the rest of the sector — from development agencies to governments to internet providers — refuses to fund, carry out, or even acknowledge the need for skill-building to accompany connectivity.

Not many organizations even recognize that missing skillsets is a problem, let alone that there is a significant difference between digital and information literacy. Far fewer devote the budget, time, effort, and training it takes to build skills to meaningfully use the internet.

A recent New York Times article, for example, documented the Marubo tribe’s rocky adoption of high-speed Starlink internet. While this was hardly the community’s first exposure to the internet (as responses to this piece have since called out), it did mark a drastic change in internet accessibility for this remote community in the Amazon rainforest, intensifying existing debates over what the internet means for their identity and culture.

On one side, proponents lauded the internet’s value in making calls to emergency health services instantaneous, in opening up new economic and educational opportunities, in facilitating connection with faraway loved ones, and in enabling the community to better advocate for itself. On the other, detractors pointed out the increased sense of cultural disconnection among teenagers glued to social media, the dangers of scams and misinformation, and the more aggressive behavior of young men since they gained easier access to pornography.

But what caught our attention most was a piece of information buried in the tail end of the article — that the project’s leaders said they planned to provide internet training but that “No Marubo interviewed said they had yet received it.” By this point the Starlink antenna had been in place for seven months. What was the hold-up? And if it does eventually happen, what will this internet training cover?

What are internet-ready skills?

The introduction of high-speed internet in remote communities underscores a crucial issue: the global need for digital and information literacy. Digital literacy allows individuals to navigate and use digital platforms effectively, while information literacy empowers them to critically evaluate and utilize information. These are essential skills for safe and productive internet use but are nearly by definition lacking in newly connected communities.

The problems arising from this gap are not trivial, and the risk is highest for those with the least experience with the internet’s information firehose. In our work with communities across the developing world, we see mis- and disinformation striking people from the first time they connect to the internet. Farmers are targeted with financial scams on WhatsApp, women and girls become the targets of sexual violence as pornography circulates, and communities are decimated by mis- and disinformation about HIV/AIDS, COVID-19 and cholera, to name a few.

As the world continues its push for wider internet connectivity, especially in remote and underserved areas, we must also advocate for responsible implementation strategies that include robust educational frameworks to combat the rise of misinformation and other digital harms.

The unique challenge of information literacy

While digital literacy involves the technical skills to use internet tools, information literacy is more complex and arguably more important. Information literacy requires a deeper, more nuanced understanding and longer training, which is often overlooked by entities eager to simply connect the unconnected. It involves the ability to discern the reliability of various information sources, an essential skill in an era dominated by digital misinformation.

Not many organizations even recognize that missing skillsets is a problem, let alone that there is a significant difference between digital and information literacy. Far fewer devote the budget, time, effort, and training it takes to build skills to meaningfully use the internet. We think it’s time for that to change.

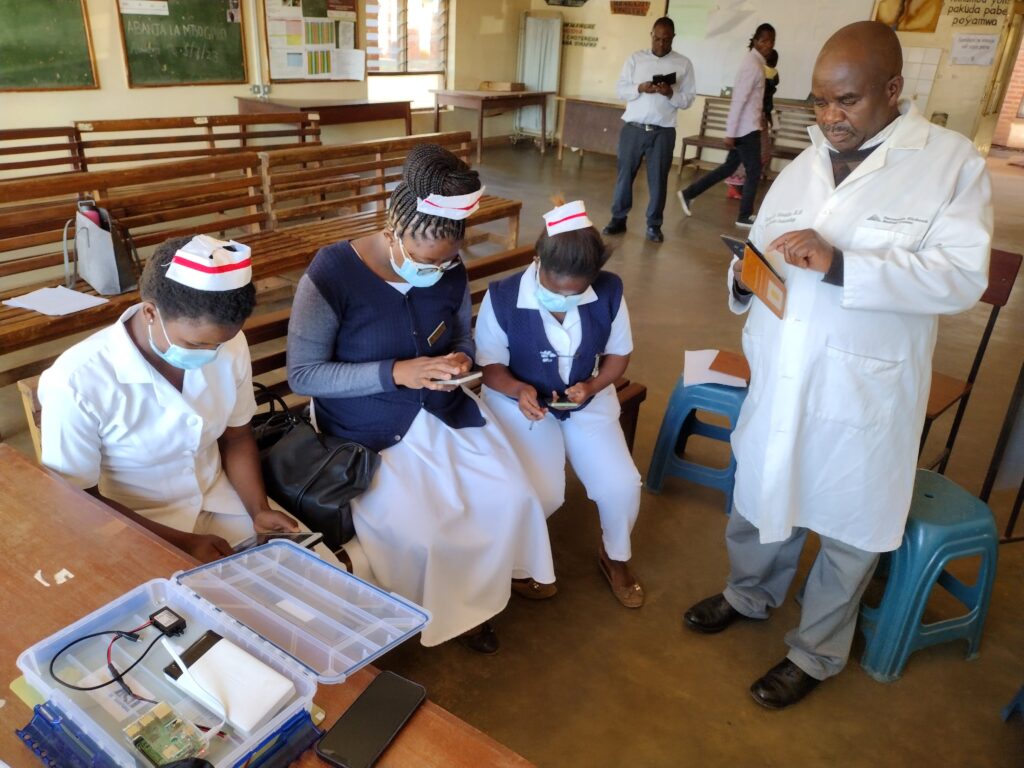

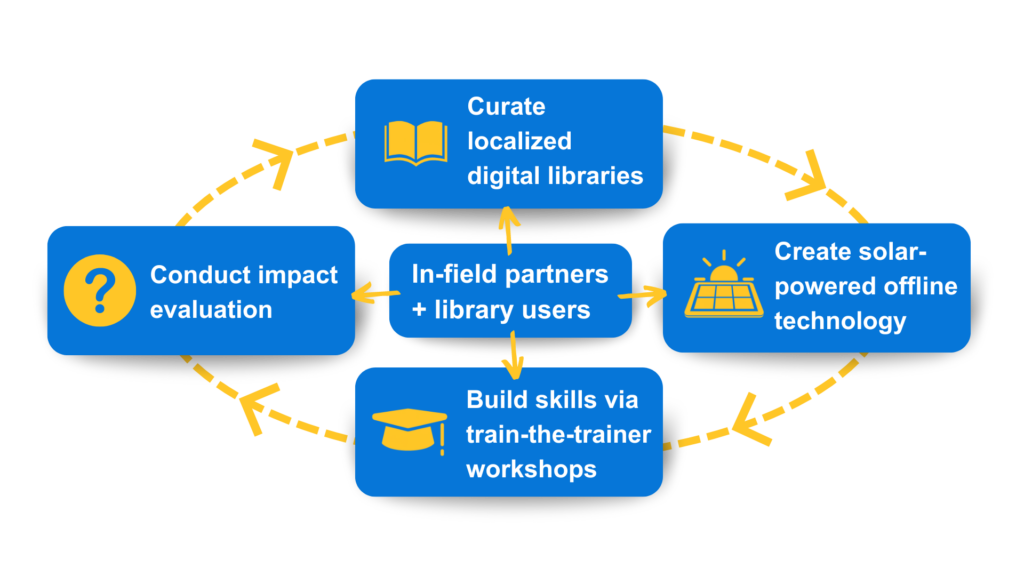

Our approach at Arizona State University’s SolarSPELL Initiative is to use solar-powered digital libraries to provide educational resources in areas without internet access. Crucially, we co-create these libraries with local partners to ensure they meet community needs and are culturally and linguistically relevant. And critical to our model is the training to ensure that digital and information literacy skills are built among community members, so that the internet can become a tool for empowerment once it reaches them.

And we know this approach is working. In interviews and surveys carried out with thousands of SolarSPELL library users, more than 80% of respondents report feeling better equipped to use the internet and other digital technologies, as well as better able to find, evaluate and use new information, as a result of using the SolarSPELL library.

As the world continues its push for wider internet connectivity, especially in remote and underserved areas, we must also advocate for responsible implementation strategies that include robust educational frameworks to combat the rise of misinformation and other digital harms. It is imperative that connectivity initiatives, especially in culturally sensitive and isolated regions like the Amazon, are paired with comprehensive information literacy programs. Only then can we ensure that the internet remains a tool for empowerment rather than a source of disempowerment.

By focusing on empowering local communities to harness the internet’s benefits safely, we can help mitigate the risks associated with digital connectivity. This approach not only respects the cultural integrity and autonomy of local populations but also contributes to a more inclusive and equitable digital future.

Sign up to have new blog posts sent straight to your inbox: